History of the

Archaeological Area of Velia

The site of Velia is the product of a long and layered history—an intricate web of events, architecture, and transformations that, over time, have overlapped, evolved, and merged. Today, Velia is part of the contemporary landscape, but it was once the heart of a vital and strategic region. Its story lies in the ability to read this deep historical layering, rooted in the distant past.

The rediscovery of Velia began in the 19th century, when the construction of the coastal railway led to the unearthing of large quantities of archaeological material—clear evidence of a significant ancient Greek city near present-day Ascea Marina (SA). Following these early discoveries, between 1886 and 1889, the German engineer W. Schleuning produced the first plan of the site, recording all the visible structures that had come to light.

Systematic excavations began only in 1927. From that point on—and despite interruptions during the two World Wars—archaeological research has continued to this day. A major milestone came in 2005 with the establishment of the Archaeological Park of Velia. In 2020, the ancient city was officially incorporated into the autonomous institute of the Ministry of Culture: the Archaeological Parks of Paestum and Velia.

The Significance of Elea

in Greek Culture

Between 500 and 450 BC, Elea emerged as one of the most flourishing cities of Magna Graecia, thanks to its vibrant maritime trade and well-established social and political structure. According to ancient sources, the city had a stable constitution attributed to the philosophers Parmenides and Zeno—founders of an influential school of thought that left a lasting mark on the intellectual and scientific traditions of the ancient world.

During the Classical period (450–350 BC), Elea experienced a golden age. Its defensive walls were extended, and the urban quarters became increasingly sophisticated. The inhabitants of Elea seafaring skills secured them not only a steady flow of goods but also valuable political alliances. One such alliance was with Rome, which relied on Velia for ships and a secure landing point during the First Punic War (264–241 BC). When Hannibal invaded Italy, Velia once again aligned itself with the Romans, affirming its status as a strategically vital city. In this same period, Velia welcomed prominent Roman figures, including the general Lucius Aemilius Paullus, renowned for his conquest of Greece.

Elea’s influence went far beyond politics and commerce. It was also a centre for learning, medicine, and philosophy. The legacy of Parmenides and Zeno—masters of ancient reasoning whose ideas continue to echo in modern thought—underscores the city’s role as a beacon of intellectual and cultural life.

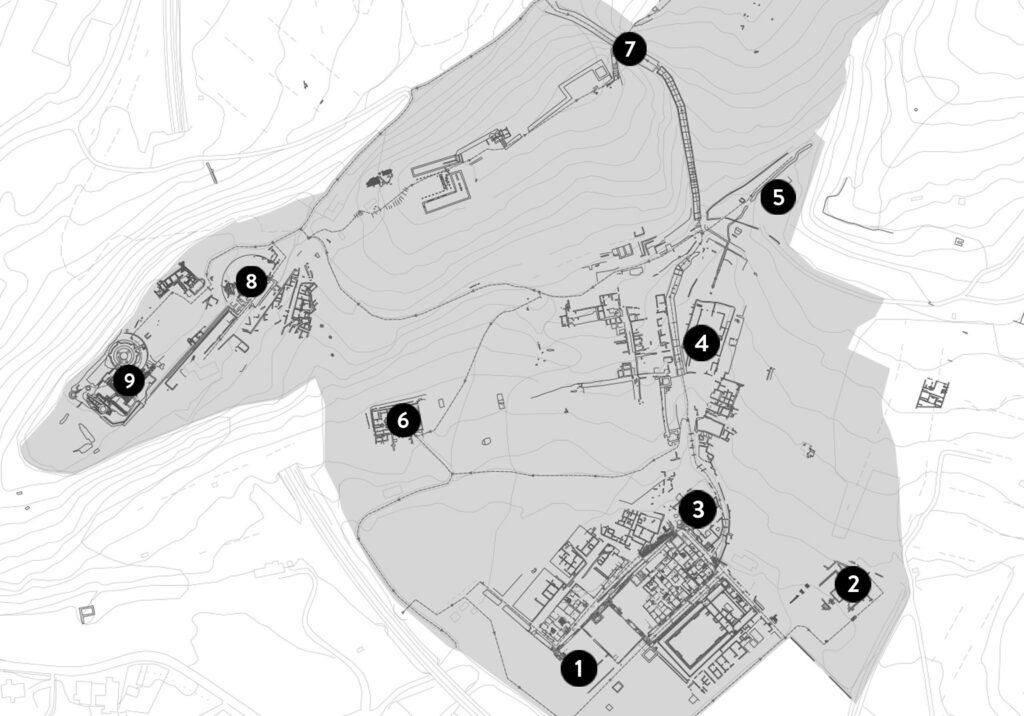

Check the Map of the

Archaeological Area

Discover the Areas of Interest in the archaeological area

Necropoleis of Porta Marina Sud

Just outside the city walls, you can still see the remains of the Roman necropoleis that developed during the early centuries of the Common Era. Excavations in this area have uncovered a wide variety of burial types. Today, small mausoleums and several funerary enclosures remain visible.

Among the finds, inscriptions recovered from some of the tombs reveal the lives of men and women once buried here. They include Mario Domitio, a veteran of the Roman fleet; Quintus Valerius Sisenna Reginus, a Roman knight who lost his life in a storm while sailing along the coast; and Caio Giulio Callisto, who died at the age of just 15, with a grave prepared by his father. One particularly touching dedication comes from Sosia Germana, who arranged a burial for her beloved husband, Ateneo, who lived to be 58.

Masseria Cobellis Complex

Situated in a strategic position between the southern and eastern quarters of the city, and close to Insula II, stands the restored 19th-century farmhouse of Masseria Cobellis. This building incorporates the remains of an ancient monumental complex dating from the 1st to 2nd centuries AD, designed over several levels around a natural spring and built to follow the contours of the land.

This elegant public structure, dating back to the mid-Imperial period, is notable for its dramatic two-level layout and its careful symmetry. At the centre of its design were a nymphaeum and a basin, framed by brick staircases and once clad in marble slabs—some of which are still partially preserved today.

Roman Baths

In the lower part of the city, just below the hills, stands a trapezoidal-shaped bath complex, built between the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. Constructed using the typical imperial technique known as opus listatum—alternating layers of stone and brick—the building was once adorned with painted plaster and elegant marble cladding. Today, remnants of the bath’s drainage channel can still be seen near the junction of Via di Porta Rosa and the southern district. During the medieval period, the semicircular basin of the calidarium was repurposed as a baptismal font.

Following the natural slope of the terrain, the baths were seamlessly integrated into the urban landscape, linking the southern district to the elevated terrace quarter. The main entrance, with its pedimented façade, faced onto Via di Porta Rosa. From the atrium, visitors would turn left to enter the apodyterium (changing room), while directly ahead lay the frigidarium, a cold-water room with a mosaic floor decorated with fantastical sea creatures. To the right were the heated spaces: the tepidarium and laconicum for warm baths and saunas, and the calidarium for hot-water immersion. In the laconicum, you can still see the terracotta tubes embedded in the walls and the suspensurae—small pillars beneath the floor designed to circulate hot air.

Askleplieion

The Asklepieion is a Hellenistic complex laid out in a striking, terraced arrangement across three levels, framed by well-defined walls and embellished with fountains and nymphaea. The lower terrace is structured around a large square (30 x 17 metres), bordered on three sides by a colonnaded portico. Entry is from the lower edge, where a grand fountain once stood—four smooth columns from it still remain.

This complex is interpreted as the sanctuary of Asclepius, the god of medicine and healing, whose statue was found in the city. Here, pilgrims would not only worship the god but also seek treatment using the spring’s healing waters. The portico of the lower terrace is believed to have housed the sick, who, after their water therapies, would rest in the open-air colonnades.

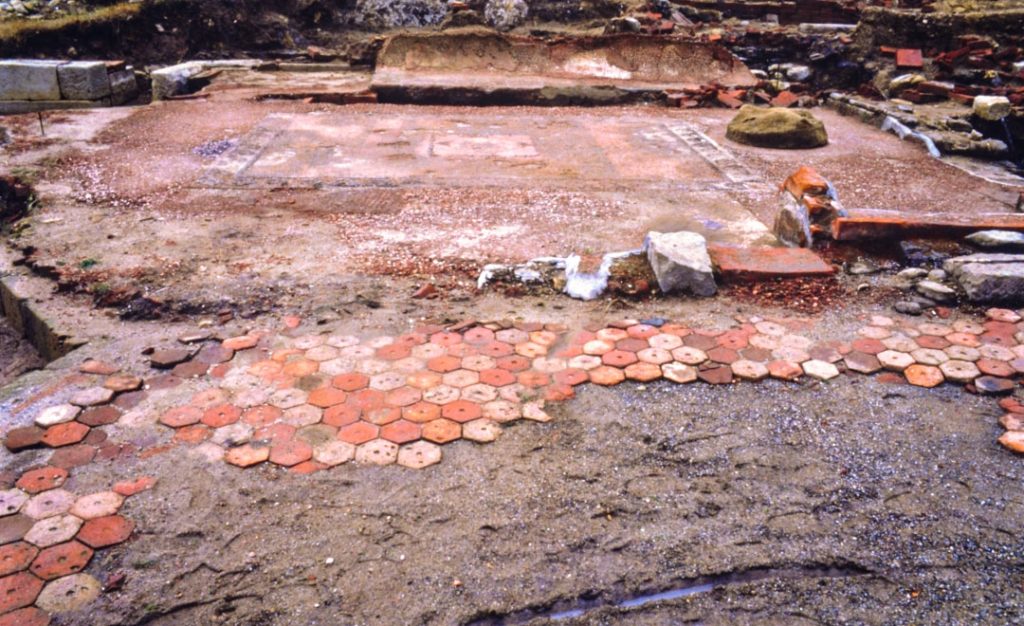

Hellenistic Baths

At the highest point of the valley, in an area once used for citrus cultivation and known locally as the “Giardiniello,” stands a thermal complex dating back to the early 3rd century BC. Known as a balaneion, this public bathhouse—open to all citizens—has no close parallels in other cities of Magna Graecia.

Three main rooms have been identified: a central changing room; a circular tholos-shaped space where seated individual baths were arranged in a circle, allowing attendants to pour hot water over bathers; and a mosaic-lined pool with benches for communal hot bathing. The remains of the furnace used to heat the water are also still visible. The Hellenistic Baths mark the top of a sequence of wellness-focused structures, which include the Asklepieion, Roman Baths, and the Masseria Cobellis complex—all devoted to health and physical care.

Casa degli Affreschi

At the western edge of the Terrace Quarter, beneath the slopes of the Acropolis, lies a large domus built around a central peristyle. Dating to the early 2nd century BC, it covers approximately 400 square metres and includes over thirty rooms grouped around two main courtyards.

Some of the main rooms still preserve their refined frescoed walls, adorned with faunal, floral, and geometric motifs. These decorative elements are particularly present in the reception rooms, reflecting the prestige and elegance of the residence. Homes like this belonged to Velia’s noble class, who lived here during leisure periods and hosted guests in a refined setting.

Porta Rosa

At the narrowest point of the gorge dividing the Velia promontory stands the city’s most iconic monument—Porta Rosa. German engineer W. Schleuning had already hypothesised the presence of an urban gate here, and it was Mario Napoli who uncovered the structure on 8 March 1964. It was named in honour of his wife, Rosa.

Porta Rosa is not, in fact, a gate but a viaduct—an architectural structure formed by a dry-stone arch with a semicircular vault, built entirely in sandstone. It marks a key point of both separation and connection in the city’s road system, linking two main routes: one running beneath the arch, joining the northern and southern city districts, and one above it, connecting the Acropolis to the ridge of the gods and the medieval fortress of Castelluccio.

To construct this impressive structure, the promontory was cut, and the slopes stabilised with massive, terraced retaining walls, still visible today on the left-hand side of the southern wall. The construction of Porta Rosa was part of a broader urban redevelopment effort that reshaped the city in the late 4th century BC.

The Theatre

In ancient Greek cities, theatrical performances were central to civic life. Audiences were often highly engaged, and plays could run throughout the day. The theatre was not only a source of entertainment, but also a means of civic education.

The theatre visible today is the result of a Roman-era reconstruction, when Velia’s Acropolis underwent major redevelopment. It could accommodate around 2,000 spectators. The theatre is built into the hillside on its western side, while the eastern part is supported by an artificial embankment. The cavea (seating area) comprises 20 to 22 rows of stone seats, divided into five equal sectors. Access was via two side entrances (parodoi). The stage was positioned in a panoramic spot and supported by the terracing wall below.

The Acropolis

The westernmost part of the Velia promontory is occupied by the Acropolis, laid out over two main terraces. The upper terrace is home to the Angevin Tower and the so-called Palatine Chapel, while the lower terrace contains the Church of Santa Maria in Portosalvo.

During the first excavations of the 1920s, this area was still covered with medieval and early modern buildings, which were gradually removed to allow exploration of earlier settlement layers.

The Acropolis has been continuously inhabited since the foundation of the Phocaean colony. On the southern slopes of the promontory, around 535 BC, a residential quarter began to develop—extensively investigated by an Austrian archaeological mission.

Simultaneously, the first structures linked to a sacred building appeared on the upper terrace. During the Classical period, around 480 BC, the upper city was entirely reorganised as a public religious area. The older residential quarter was abandoned and buried beneath a large terrace, upon which a major sanctuary was constructed—likely dedicated to the goddess Athena.

Thanks to ongoing excavations, we now have a clear picture of how the sanctuary may have looked during the Hellenistic period, when extensive renovations introduced several monumental elements: the theatre built into the natural slope, the sanctuary’s entrance near the Palatine Chapel, the large temple (of which the foundation is still visible), a porticoed building to the west of the temple, and a stoa (covered walkway) adjoining the lower terrace’s retaining wall.

Discover the other areas of Velia

I Parchi archeologici di Paestum e Velia sono un istituto del Ministero della Cultura dotato di autonomia speciale, iscritto dal 1998 nella lista del patrimonio mondiale UNESCO.

The Archaeological Parks of Paestum and Velia; an institute of the Ministry of Culture, with special autonomy and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998.